An Esthetic Makeover With Lithium Disilicate Veneers

Using an integrated laboratory communication platform can streamline treatment, improve outcomes

Isam Estwani, DDS | Navneet Josan, DDS | Joe Apap, CDT, TE, MDT

The creation of appealing facial esthetics is one of the primary goals of patients seeking elective dental care.1,2 The smile has a major impact on the perception of facial esthetics.3 Unfortunately, in many situations, dentists limit themselves by only considering the intraoral area. Correctly restoring teeth is just part of the process of making them esthetically pleasing. Esthetic dentistry should not begin or end inside the lips; the teeth need to fit the entire framework of the face.4 The ability to change the dentofacial form through esthetic dentistry requires an understanding of facial beauty, which includes the evaluation of facial esthetics, proportions, and symmetry.5-7 Furthermore, the communication of this vital information throughout the production process is critical to success.

Every successful treatment plan involves clear, streamlined communication. The traditional process of writing down a prescription, taking a few photographs, and drawing some illustrations has been replaced by the use of advanced technology. The development of integrated practice/laboratory communication platforms driven by artificial intelligence (AI) has streamlined treatment planning. With these enhanced communication platforms, dentists and laboratories can efficiently achieve patients' desired results while reducing the number of appointments required. Such platforms can also minimize the cost of treatment as well as the overall time spent on cases by both dentists and laboratory technicians. The following case report demonstrates the application of an integrated practice/laboratory communication platform to improve outcomes.

Case Report

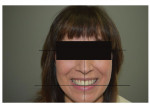

A 40-year-old female patient presented to the practice with concerns about the appearance of her teeth. She reported that it was difficult for her to feel confident and smile openly and that she wished to receive an esthetic smile makeover. Upon examination, significant dissymmetry was observed among the heights of the patient's gingival zeniths, which imparted an asymmetric appearance to her smile (Figure 1). In addition, the maxillary anterior teeth that were visible in her smile were more than two shades darker than her mandibular anterior teeth, and her horizontal plane was also higher on the left side.

Treatment Planning

After a thorough examination, a treatment plan was recommended that included laser gingivectomy at time of the preparation for teeth Nos. 7 through 10 to correct the gingival height dissymmetry, followed by the placement of layered lithium disilicate veneers to restore her esthetics. The patient agreed to the treatment plan, which would involve a provisionalization period prior to the fabrication and placement of the final veneers.

To begin, pretreatment photographs were taken (Figure 1), including a stick bite photograph (Figure 2), and an intraoral scan was acquired (iTero Element™, Align Technology). It was decided that tooth No. 8 was appropriate to serve as a guide to determine the ideal length, width, and overall shape of the restorations as well as the proper gingival contour; therefore, its measurements were acquired (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The pretreatment photographs, intraoral scan data, and tooth No. 8 measurements were sent to the laboratory along with additional instructions through the practice's integrated online laboratory communication platform (Cayster Dental Technology Platform, Cayster).

Once the laboratory received the records on their end of the online platform, they began designing the patient's new smile. The pretreatment photographs were imported into virtual smile design software (3Shape Smile Design, 3Shape), and the technicians used the patient portrait to plot an interpupillary line, a facial midline, and a line parallel to the interpupillary line across the incisal plane of the upper anterior teeth (Figure 5). These lines were then transferred to the pretreatment scan of the patient, and additional lines were added to show the desired incisal lengths and gingival heights (Figure 6). Teeth Nos. 9 and 10 would undergo greater gingival recontouring so that their gingival zeniths would match those of teeth Nos. 8 and 7, respectively. Also, this would lower the patient's smile line starting from tooth No. 8 so that it would be symmetrical bilaterally with the incisal plane line. The laboratory respected the 11.5 mm length of tooth No. 8 and used the gingival height of tooth No. 7 as a limiting factor in establishing the proportions of the smile design. Once complete, the laboratory submitted the smile design to the clinicians, and after a few requested minor adjustments were made through the instant messaging feature of the online communication platform, the design was able to be finalized in a matter of minutes (Figure 7).

Following approval of the smile design, it was converted to STL format and sent to the 3D printer (Einstein™ 3D Dental Printer, Desktop Health). The preoperative model and opposing arch were also printed for mounting on a semi-adjustable articulator (Panadent PSH, Panadent) using a facebow mounting jig sent from the practice. Magnetic plates were used, and both the smile design and preoperative models were split-mounted to the opposing arch. At the request of the clinicians, the smile design model was used to fabricate several silicone matrices (Sil-Tech® impression putty, Sil-Tech), including a palatal matrix and a facial matrix to show that adequate reduction was achieved during preparation as well as a full coverage matrix to use for the chairside fabrication of the temporary restorations. The laboratory also fabricated a clear reduction guide. These were delivered to the clinicians for the next phases of treatment.

Preparation and Provisionalization

When the patient returned to the practice, local anesthesia was administered to numb the area that would be treated. First, the soft-tissue recontouring would be addressed. In the smile design plan, it was made certain that the ideal proportions of length and width of the restorations established in the smile design would be maintained using the clear reduction guide, which also showed the proposed gingival lines. Because the gingival recontouring of tooth No. 10 would be the most significant, the bone was sounded with a periodontal probe, and it was established that removing the soft tissue to the desired line would keep our margins 2.5 mm away from the bone, respecting the biologic width. A diode laser was used to perform the soft-tissue recontouring, which was then verified using the clear index (Figure 8).

Once the soft-tissue recontouring was complete, teeth Nos. 4 through 13 were prepared for veneering. To begin, a 0.5-mm depth cutting bur was used across the facial surfaces of teeth Nos. 4 through 13 to make horizontal cuts that were 4 mm apart (Figure 9). Then, the incisal reduction was performed using a 1.5-mm depth cutting bur. Next, coarse- and fine-grit diamond burs were used in succession to prepare each tooth down to the depth cuts, ensuring that all of the sharp edges were eliminated (Figure 10). The palatal and facial putty matrices were then used to verify that adequate reduction had been achieved (Figure 11). After the preparations were finished, they were photographed, and stump shades were acquired (Figure 12 and Figure 13). A latex-free lip and cheek retractor (OptraGate®, Ivoclar) was then placed, and retraction paste (Traxodent®, Premier Dental) was injected into the gumline of all the preparations and left for 1 minute. An intraoral scan of the preparations was then acquired.

Next, the provisional restorations were made chairside using a self-curing provisional material (Luxatemp® Plus [B1], DMG America). The material was injected into the silicone index provided by the laboratory and then fully seated in the patient's mouth over the veneer preparations (Figure 14). Although the shade of the final veneers would be 0M2 (VITA Bleachedguide 3D-MASTER®, VITA Zahnfabrik), a slightly darker shade was chosen for the provisional restorations, which was also approved by the patient. When the provisional restorations were finished, the patient stated that she was very happy with the outcome (Figure 15). With her approval, a new intraoral scan of the provisional restorations was acquired and then uploaded to the integrated laboratory communication platform along with the preparation scan, preparation photographs, stump and final shade information, and layering instructions for fabrication of the final lithium disilicate veneers.

Fabrication of the Final Veneers

The laboratory received all of the new records and instructions from the practice through the integrated platform, so everything that was needed to continue with the case was there in the patient case file. After the new records were imported into the smile design software, the smile design was finalized and used to create the individual veneers. A virtual articulator was used to check for any lateral interference, a few simple adjustments were made based on the criteria set forth by the clinicians, and the case was ready for fabrication. Next, STL files were created and sent to a mill (DWX, Roland DGA) to mill the wax that would be used to press the lithium disilicate glass-ceramic ingots into veneers. Because some of the preparations demonstrated a darker stump shade of ND3, a low translucency lithium disilicate ingot was selected (IPS e.max® Press LT [BL1], Ivoclar) to offset it. All of the margins were sealed on the printed model and dies of each veneer preparation, and the wax-ups were then sprued and invested using a phosphate-bonded universal investment material (IPS® PressVEST, Ivoclar) and a 300 g ring. The ring was placed in a furnace (Programat® EP 5010, Ivoclar) for pressing. After the pressing cycle was complete, the veneers were carefully divested and placed into a stone cleaner solution in an ultrasonic cleaning machine that was run for 5 minutes. The pressed veneers were then carefully separated from the sprues for final contouring, layering, staining, and glazing.

After the veneers were separated, they were placed on the soft-tissue model, the contacts were checked and adjusted where needed, and the silicone index was used to confirm the incisal length (Figure 16). The model was mounted on the articulator, and the occlusion was checked in centric, lateral, and protrusive movements. Next, the incisal third of the veneers was cut back, mamelons were created, and teeth Nos. 6 through 11 were layered with shaded add-on material (IPS e.max Ceram Add-On Incisal, Ivoclar) for a more vital and lifelike appearance (Figure 17). Final staining and glazing were then performed (Programat® P710, Ivoclar) to achieve the final 0M2 shade that the patient requested, and once the result was confirmed using the ND2 and ND3 stump-shaded dies, the veneers were returned to the soft-tissue model for a final check of the contacts and occlusion (Figure 18). An etchant (IPS Ceramic Etching Gel, Ivoclar) was applied to the intaglio surfaces of the veneers to pre-etch them, but the clinicians were instructed to refresh this etch when they were ready to seat the veneers.

The Seating Appointment

After receiving the final veneers from the laboratory and checking them on the model, the clinicians prepared the patient for final seating by removing the provisional restorations and thoroughly cleaning the area (Figure 19 and Figure 20). The veneers were then tried in (Variolink® II Try-In Paste, Ivoclar) to check their contacts and general esthetics. The patient gave her approval to proceed.

To optimize the bond strength, a total etch approach was selected. Once a retractor was placed, and rubber dam isolation was achieved to maintain a dry field, an etchant was applied to the prepared tooth surfaces for a total of 30 seconds and rinsed away, and the preparations were air-dried (Figure 21). Next, a two-component primer (Multilink® Primer A+B [1:1 ratio], Ivoclar) was mixed, applied to the dentin and enamel surfaces, and scrubbed with light pressure for 15 seconds (Figure 22). The primer was then allowed to sit for 30 seconds, and the preparations were air-dried. This primer was self-curing, so no light-curing was needed. To prepare the veneers, their intaglio surfaces were refreshed using a hydrofluoric acid etchant (IPS Ceramic Etching Gel, Ivoclar) for 10 seconds, which was then rinsed and dried until the intaglio surfaces appeared frosty white. The veneers were then silanated with a single-component primer (Monobond-S®, Ivoclar).

With the teeth and restorations prepared, the final seating began with the two central incisors (teeth Nos. 8 and 9). The intaglio surfaces of the veneers were loaded with resin cement (Variolink® Veneer, Ivoclar), they were firmly seated into position, and the excess cement was swabbed away. Once the margins were checked to ensure that they were sealed, the tooth No. 8 and 9 veneers were held in position while their cervical aspects were light-cured for 5 seconds to tack them in place. This procedure was continued on the lateral incisors next, and the remaining veneers were placed two at a time bilaterally until all of them were seated. An oxygen barrier solution (DeOx™, Ultradent) was then applied to prevent the formation of an oxygen-inhibited layer and ensure a complete cure of any exposed cement. Following the initial cleanup, glycerin was placed on all of the margins, and the veneers were completely light cured for 20 to 30 seconds per surface. All of the remaining excess cement was then cleaned away, and a serrated instrument was used to separate the contacts. Floss was also used to help loosen and remove any uncured cement in the interproximal spaces; however, the clinicians made certain to slide it out instead of pulling it down to prevent dislodging of the veneers. A No. 12 blade scalpel was also helpful in removing the interproximal cement. The clinicians checked for any occlusal interference in centric relation and protrusive movements and made some slight adjustments using a football-shaped diamond bur. Any remaining cured interproximal cement was removed using a long tapered fine diamond bur. After the interproximal surfaces were polished with a diamond impregnated strip, a final polish was performed with diamond impregnated rubber points and cups (Figure 23). The patient was handed a mirror, and she stated that she was ecstatic with the results (Figure 24).

Conclusion

The patient's reluctance to smile was immediately resolved after the provisional restorations were placed. She noted that she was already pleased with the appearance of her new smile. Once teeth Nos. 4 through 13 were fully restored, the patient's confidence was fully restored, enhancing her quality of life. She was advised to maintain proper oral hygiene practices, including brushing and flossing daily and attending regular dental check-ups, to ensure the long-term success of the treatment. She has been seen several times since the final veneer seating, and she continues to report how happy she is with the results.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Town & Country Dental Studios in Freeport, New York, for performing the laboratory work on this case.

About the Authors

Isam Estwani, DDS

Fellow

Academy of General Dentistry

Private Practice

Herndon, Virginia

Navneet Josan, DDS

Private Practice

Woodbridge, Virginia

Joe Apap, CDT, TE, MDT

Technical Support Manager

Creodent

New York, New York

References

1. Machado AW. 10 commandments of smile esthetics. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014;19(4):136-157.

2. Mack MR. Perspective of facial esthetics in dental treatment planning. J Prosthet Dent.1996;75(2):169-176.

3. Havens DC, McNamara JA Jr, Sigler LM, Baccetti T. The role of the posed smile in overall facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 2010;80(2):322-328.

4. Greenberg JR, Bogert MC. A dental esthetic checklist for treatment planning in esthetic dentistry. Compend Contin Educ Dent.2010;31(8):630-638.

5. Shah R, Nair R. Comparative evaluation of facial attractiveness by laypersons in terms of facial proportions and equate it's deviation from divine proportions - a photographic study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2022;12(5):492-499.

6. Apa M. Facial esthetics-the framework. Inside Dentistry.2012;8(2):60-67.

7. Pisulkar S, Nimonkar S, Bansod A, et al. Quantifying the selection of maxillary anterior teeth using extraoral anatomical landmarks. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27410.