In-Office Bleaching with a Multi-Intensity Whitening Lamp

Patients who demand rapid results experience exceptional outcomes

Various materials, techniques, and devices have been used in dentistry for treating discolored teeth with varying amounts of success.1

As early as 1884, for example, hydrogen peroxide was used to treat discolored pulpless teeth.2 The primary indication for these early whitening techniques was typically limited to the severely discolored, nonvital single tooth. These techniques required multiple treatments, often leading to unpredictable results.

Since the introduction of the nightguard vital custom bleaching tray technique in 1989, treatment of multiple vital teeth has become common practice with more predictable results.3 Although the treatment of discolored vital teeth became more predicable with professionally dispensed at-home whitening trays, these methods still require multiple days or weeks of treatment to reach satisfactory results. For this reason, power bleaching, especially with the use of adjunct light, has become the treatment of choice for patients who expect rapid results.

Power bleaching, or professional in-office bleaching, is a term used to describe the treatment of discolored dentition with a high concentration peroxide agent applied by the dentist at chairside. The primary focus of this article will be to present the power bleaching technique with a multi-intensity adjunct light for the purpose of achieving immediate whitening results on multiple vital teeth.

Case Presentation

A 14-year-old female patient presents with the chief complaint of yellow teeth and the desire to achieve a whiter smile. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed no existing restorations in the esthetic zone, no decay, and the presence of healthy gingival tissues. White spot lesions from orthodontic treatment were noted. The patient was informed that white spots immediately following treatment may appear accentuated while teeth were dehydrated. Advantages and disadvantages of in-office and at-home whitening were reviewed with patient. Due to patient’s immediate desire for results, the in-office whitening option was requested. Because of the young age of the patient and to minimize tooth sensitivity, 600 mg of ibuprofen was supplied 30 minutes prior to treatment.4

Clinical Protocol

Tray Impressions

Impressions of the patient’s teeth were taken at the start of the in-office power bleaching appointment. This allowed for the fabrication of custom bleach trays to supplement the in-office procedure with at-home whitening, if desired, or for use in future maintenance treatment. A patient can also wear the custom tray out of the office loaded with a desensitizing gel if tooth sensitivity is experienced following the procedure.

Prophy

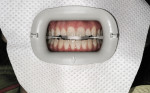

Superficial stains and plaque were first removed using a prophy paste in a rubber polishing cup (Figure 1).

Initial Shade

The pretreatment shade was documented with photography and a visual shade guide designed for monitoring bleaching results (VITA Bleachedguide 3D-Master®, Vident, https://vident.com) used under color-corrected light (5500K, color-rendering index >90). The initial shade selected, 3M2, provided a reference for demonstrating the color change to the patient when compared with the post-treatment shade (Figure 2).

Light Protective Glasses/Light Guides

The patient was provided with light-filtering eyewear to protect from exposure to direct blue light. A protective light guide surrounding the exit window of the bleaching lamps was used as recommended in the literature to protect the operator from scattered optical radiation when using a supplemental light5 (Figure 3).

Lip Protection/Cheek Retraction

Vitamin E oil, which can aid in neutralizing accidental soft tissue contact with the peroxide, was applied to the lips prior to inserting the cheek/lip retractors. A sunblock cream may be used as an alternative if the lamp is suspected to include ultraviolet emission. A retractor that shields the lips from the light and guards the tongue from bleaching agent was used (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The protective bib/isolation napkin was slipped over the retractors to further shield the perioral skin (Figure 6).

Gingival Isolation

Isolation to protect the gingiva from chemical burn and light radiation was achieved by placing long cotton rolls in the vestibules, followed by careful application of a light-cure resin barrier material. A small needle-tube syringe was used initially to scallop at the gingival crest, two teeth at a time, and tack cured for 2 to 3 seconds. A larger lumen tip was used to extend the additional resin barrier material apically to seal against the cotton rolls (Figure 7). Final curing of the barrier was achieved by waving the light tip back and forth for 1 to 2 minutes per arch (Figure 8). Any remaining exposed soft tissue in vestibules was covered using unfolded gauze squares.

Application/Light Activation of Bleach

A 25% hydrogen peroxide, two-component bleaching agent (Philips ZOOM, Philips Oral Healthcare, www.philipsoralshealthcare.com) was applied to the teeth at a thickness of 1 to 2 mm through an automix tip of the dual-barrel syringe and evenly spread with an applicator brush (Figure 9 and Figure 10). A multi-intensity (low: 60 mw/cm2, medium: 120 mw/cm2, high: 190 mw/cm2), blue LED whitening lamp was used to illuminate the bleaching agent (465 nm wavelength; Philips ZOOM WhiteSpeed, Philips Oral Healthcare). The light guide attached to the lamp head was aligned with the positioning tabs located on the left and right sides of the cheek retractors.

The patient received two 15-minute applications of bleach and light on high intensity (190 mw/cm2), followed by the application of a desensitizing gel containing amorphous calcium phosphate, 5% potassium nitrate, and 1.1% fluoride (Relief ACP Oral Care Gel, Philips Oral Healthcare) applied to the lingual of the mandibular incisors where minor tooth sensitivity was reported. The intensity was reduced to medium (120 mw/cm2) for two additional 15-minute applications of bleach and light. Surgical suction was used rather than high-volume suction to remove the bleach between applications to avoid bleach splatter and dislodging of the resin barrier material (Figure 11).

Remove Barrier

Following the completion of the last bleaching session, the resin barrier was dislodged with an explorer and removed as one unit by grabbing the attached cotton rolls (Figure 12).

Post-Treatment Shade and Instructions

The post-treatment shade was recorded as 1M1 and photographed to demonstrate the immediate color change to the patient. This translates to a change of 12 shades guide units from 3M2 to 1M1, according to the 29-step Vita Bleachedguide and American Dental Association guidelines for monitoring whitening6,7 (Figure 13 and Figure 14). Instructions were provided to wait a minimum of 6 hours after in-office bleaching before drinking any chromogenic drinks such as coffee or grape juice.8 The patient was also provided a custom tray loaded with desensitizing gel to wear when leaving the office and instructed to take an addition 600-mg dose of ibuprofen following the appointment to continue management of tooth sensitivity.4

Summary

The popularity of tooth whitening has led to a variety of bleaching methods from which to choose. The demand for single-visit whitening treatment for patients who expect rapid results continues to be high. In the current case, improved whitening of 12 shade guide units was achieving as a result of a single in-office treatment using 25% hydrogen peroxide with a multi-intensity blue LED whitening lamp.

References

1. Barghi N. Making a clinical decision for vital tooth bleaching: at-home or in-office? Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1998;19(8):831-8.

2. Harlan AW. The removal of stains from teeth caused by administration of medical agents and the bleaching of pulpless tooth. Am J Dent Sci. 1884/1885;18:521-524.

3. Haywood VB, Heymann HO. Nightguard vital bleaching. Quintessence Int. 1989;20(3):173-176.

4. Charakorn P, Cabanilla LL, Wagner WC, et al. The effect of preoperative ibuprofen on tooth sensitivity caused by in-office bleaching. Oper Dent. 2009;34(2):131-135.

5. Bruzell EM, Johnsen B, Aalerud TN, et al. In vitro efficacy and risk for adverse effects of light-assisted tooth bleaching. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2009;8(3):377-385.

6. Paravina RD, Johnston WM, Powers JM. New shade guide for evaluation of tooth whitening—colorimetric study. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2007;19(5):276-283.

7. American Dental Association. ADA program guidelines for dentist dispensed tooth bleaching products. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; Forthcoming 2013.

8. Ontiveros JC, Eldiwany MS, Benson B. Time dependent influence of stain exposure following power bleaching. J Dent Res. 2008;87(Spec Iss B):1083.