A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Indirect Esthetic Treatment of Diastemata

John R. Calamia, DMD; Christine Sina Calamia, DDS; Kenneth S. Magid, DDS; Marta Berrazuenta, DDS; Jerome M. Sorrel, DMD

Abstract

Even if clinicians possess a basic body of knowledge in cosmetic dentistry and skills in esthetic dentistry, many cases that present on a day-to-day basis simply cannot be restored to both the clinician’s and the patient’s expectations without incorporating the perspectives and assistance of several dental disciplines. Because the success of highly-demanding esthetic cases is determined by patient satisfaction, a thorough understanding of patient expectations is necessary in order to develop a treatment plan that is ideally suited for the individual patient. To facilitate the treatment planning of multidisciplinary, indirect cases the use of the new New York University (NYU) Smile Evaluation Form can enable a thorough clinical analysis of the patient’s existing dentition, as well as an esthetic evaluation of the patient that takes into consideration the patient’s idea of what they hope to see as a final result of their dental treatment. This article demonstrates the use of this form in treatment planning a case that required coordination of orthodontic, periodontal, oral surgery, endodontic, and restorative components to ensure the predictability of the definitive all-ceramic crown and veneer restorations.

In today’s modern practice of dentistry, it is no longer acceptable to just repair individual teeth. More and more patients are demanding a final appearance that is not only physiologically and mechanically sound, but also esthetically pleasing.1 Therefore, as a result of a heightened esthetic awareness of our patients, a basic body of knowledge of the cosmetic dental treatment of teeth is necessary.2 However, even with skills in esthetic dentistry, many cases that present on a day-to-day basis simply cannot be restored to both the clinician’s and the patient’s expectations without incorporating the perspectives and assistance of several dental disciplines. Further, it has been repeatedly noted that esthetic restorative success is defined by patient satisfaction. Therefore, such cases are predicated on a thorough understanding of patient expectations in order to develop a treatment plan that is ideally suited for the individual patient.

Recently a multidisciplinary, indirect case was treatment planned using a new clinical evaluation form developed at the New York University (NYU) College of Dentistry. This form enables a thorough clinical evaluation of the patient’s existing dentition, as well as an esthetic evaluation of the patient that takes into consideration the patient’s idea of what they hope to see as a final result of their dental treatment. Adapted from the works of Abrams, Levine, and Fradeani, the form also includes areas for identifying variations from the norm.3,4,5 Additionally, the NYU evaluation form incorporates esthetic principles that have been developed in dentistry during the past 100 years, as well as newer concepts that are now considered key components of an attractive smile.3,4,5

The use of this form for planning the patient’s all-ceramic crowns and porcelain veneers also made it quite easy to identify those specialty disciplines (eg, periodontics, orthodontics) that would be necessary for the patient’s comprehensive treatment. The final clinical result speaks volumes regarding the importance of this type of treatment sequencing and organization to address existing problems that could impact the clinical, functional, and esthetic longevity of the anticipated indirect restorations.

This article explains the step-by-step clinical application of a multidisciplinary treatment as coordinated and planned using the NYU Smile Evaluation Form. The treatment ultimately produced an ideal clinical result using indirect all-ceramic crown and porcelain veneer restorations.

Case Presentation

The patient is an African American female lawyer in her mid-20s who is in the public eye on a daily basis (Figure 1). Upon presentation, her chief complaints and expectations included not liking the “dark” front tooth; not liking the “big space” between her teeth (Figure 2); and a desire for straight, white teeth that look natural for her (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

It became immediately apparent to the clinician that this case would require the involvement of specialists from multiple dental disciplines in order to produce the restorative and esthetic makeover that the patient was describing. A conservative and biologically sound interdisciplinary treatment plan needed to be developed.

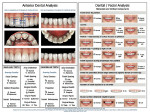

After a preliminary medical history was taken and caries risk assessment was performed, a thorough extra- and intraoral examination was conducted with the help of the new NYU Smile Evaluation Form (Figure 5). This form provided the patient with an opportunity to identify her chief complaints, while prompting the clinician to record information obtained from the facial analysis, occlusal analysis, and phonetic analysis. Side B of this form promotes an exploration of the case in greater detail by allowing the clinician to draw problem areas directly on diagrams of the anterior dentition, as well as providing horizontal and vertical components of the dental and facial analysis (Figure 6).

Additionally, a lateral facial evaluation would enable recognition of the Rickets E-Plane, as well as the nasolabial angle (Figure 7). A cephalometric radiograph showing the patient’s skeletal form would also be a necessary component of the esthetic work-up (Figure 8).

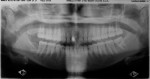

After the smile analysis was completed, the immediate problems recorded included a maxillary dental midline shift to the patient’s left and gingival zenith discrepancies in the maxillary anterior teeth (Figure 9). Additionally, although the axial inclinations of these teeth seemed to be within normal limits, this inclination needed to be preserved even if orthodontic movement was considered (Figure 10). A high lip line contributed to the need for possible gingival contouring to improve the gingival zeniths. Tooth No. 8, described by the patient as “dark,” tested non-vital. A full-mouth series of radiographs showed no active caries (Figure 11), but for tooth No. 8 it was determined that root canal therapy was prudent considering the investment in the planned indirect restorations. Therefore, the following disciplines needed to be considered for this case: endodontics, oral surgery, orthodontics, periodontics, and restorative dentistry.

Treatment Sequence

Endodontics

Despite a lack of physical symptoms, the benefit of prophylactic endodontic therapy was explained to the patient, and root canal therapy was performed on tooth No. 8. This would better assure the longevity of the root and the indirect restoration that it would eventually support. A titanium-based composite core material was used to restore the endodontic access, since enough tooth structure remained following access to ensure core strength. This had the effect of slightly lightening the root because the material is white opaque. Since a cast or prefabricated metal post was not used, this would prevent metal show-through when an all-ceramic crown would be placed as the final restoration (Figure 12).

Oral Surgery and Periodontal Considerations

Laser frenectomy, laser gingival recontouring, and gingival troughing around tooth preparations were all essential procedures to ensure the esthetics of the final treatment result. In evaluating the patient’s smile, the low attachment of the maxillary frenum was believed to be involved in the cause of the patient’s diastema (Figure 13). Without correcting this condition, permanently closing the diastema—either orthodonically or restoratively—would not have been possible. The only question concerned when to perform the frenectomy.

The decision was made to perform the frenectomy using a CO2 lasera prior to closing the diastema (Figure 14). Performing the frenectomy at this stage provided a number of advantages, including access to remove the reticular fibers between the teeth and elimination of the separating force of the frenum while closing the diastema periodontally. Since there are significantly lower numbers of myofibroblasts in a laser wound, there is a minimal degree of wound contraction and scarring that would inhibit tooth movement. Healing occurs within 10 to 14 days, with little or no scar tissue formed.6,7,8

Orthodontic Treatment

Simply stated, the orthodontic component of this treatment plan was to reposition the teeth so that the midline position could be improved and the final tooth position would allow the Golden Proportion to be achieved in the definitive restorations. After the patient underwent the laser frenectomy, brackets were placed on the six maxillary anterior teeth. A 0.016 stainless steel arch wire (Figure 15 and Figure 16) and power chain were used to begin closure of the spaces. In the following visits, the arch wire was upgraded to a 0.018 stainless steel, and again a power chain (Figure 17) was used from lateral to lateral. Once the diastemata had begun to close, with only a small space still present, a figure eight plastic wire was used to hold the position of the centrals (Figure 18). This would allow movement of the lateral incisors more mesially.

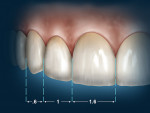

The power chain was used from right lateral to right central, and from left lateral to left central, allowing movement of both laterals mesially. The centrals were now too close together to allow the Golden Proportion (Figure 19). Therefore, they now were moved more distally.

After the spaces were redistributed to allow for the requirements of the planned restorations, small closed coil springs (Figure 20) were used to hold the final position. The brackets were then debonded, an impression was taken, and an Essex appliance was designed for short-term retention. The result attained from orthodontic treatment now enabled minimal preparation (ie, reduction) of those teeth to be treated with indirect restorations.

Periodontal Considerations

Once the final orthodontic positioning of the teeth had been accomplished, gingival zenith repositioning was necessary before initiating the restorative phase. The gingival contours for the final veneers were established using a diode laserb (Figure 21). The laser gingivoplasty narrowed the remaining interdental papilla between the central incisors and created the ideal gingival zenith to reflect the new facial contours and angulations. Since there is no recession when a gingivoplasty is performed using a diode laser, the procedure was performed at the same visit as the veneer preparation and impression taking (Figure 22).

Restorative Considerations

The treatment plan called for all-ceramic crowns on teeth Nos. 8 and 9 and porcelain veneers on teeth Nos. 5 through 7 and 10 through 12 (Figure 23) to establish a Golden Proportion of size and form for the maxillary anterior teeth, without any spacing. It is important to note that the mesiogingival preparations of the shoulder of teeth Nos. 6 through 9 were accomplished slightly subgingival (Figure 24). This provided the laboratory with room for gingival contouring in these areas, which would be slightly over-contoured in the emergence profile to allow a pushing and eventual shaping of the gingival papilla; these areas would become more pointed and less flat (Figure 24 and Figure 25). A high-strength feldspathic porcelain was used for the fabrication of the final restorations, which provided an uncompromised restorative and gingival result (Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32). The restorations were cemented using a dual-cured resin cementc that was applied in dual-cure mode for the crowns on teeth Nos. 8 and 9 and light-cured in the same shade to cement the porcelain veneers on teeth Nos. 5 through 7 and 10 through 12.

Conclusion

A multidisciplinary approach was used in this case to successfully address the many dental needs of this patient, a lawyer in the public eye on a daily basis. By initiating the treatment planning phase with the use of an evaluation form that takes into consideration the clinician’s and patient’s ideal physiological, mechanical, and esthetic outcomes, dentists can better facilitate the planning process of multidisciplinary cases and, therefore, deliver a higher level of care to their patients than ever before.

Disclosure

Kenneth S. Magid, DDS, occasionally speaks for Opus Dental Laser Products and receives an honorarium for those presentations.

References

1. Spear FM, Kokich VG. A multidisciplinary approach to esthetic dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:487-505, x-xi.

2. Calamia JR, Wolff MS, Simonsen RJ. Preface. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:xv-xvi.

3. Abrams L. Smile Evaluation Form. 255 South Seventeenth St, Philadelphia, PA 19103;1987.

4. Levine JB. Go Smile Aesthetics. 923 5th Avenue, New York, NY 10021.

5. Fradeani M. Esthetic rehabilitation in fixed prosthodontics. In: Esthetic Analysis: A Systematic Approach to Prosthetic Treatment, Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Pub. Co.; 2004:323-325.

6. Zeinoun T, Nammour S, Dourov N, et al. Myofibroblasts in healing laser excision wounds. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:74-79.

7. Magid KS, Strauss RA. Laser use for esthetic soft tissue modification. Dent Clin North Am. 2007;51:525-545, xi.

8. Gherlone EF, Majorana C, Grassi RF, et al. The use of 980-nm diode and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for gingival retraction in fixed prostheses. JOLA. 2004;4:183-190.

a Opus 20, Lumenis®, Inc., Santa Clara, CA

b Diolase Plus™, Biolase, Irvine, CA

c Variolink®, Ivoclar Vivadent, Amherst, NY

About the Authors

John R. Calamia, DMD

Director of Esthetics in the Department of Cariology and Comprehensive Care

New York University College of Dentistry

New York City, New York

Christine S. Calamia, DDS

General Practice Resident

Long Island College Hospital

Brooklyn, New York

Kenneth S. Magid, DDS

Associate Clinical Professor/Director of Predoctoral Laser Dentistry

Department of Cariology and Comprehensive Care

New York University College of Dentistry

New York City, New York

Marta Berrazuenta, DDS

Postgraduate Education Student, International Program in Orthodontics

New York University College of Dentistry

New York City, New York

Jerome M. Sorrel, DMD

Clinical Professor in the Department of Orthodontics

New York University College of Dentistry

New York City, New York