Intentional Replantation: Does It Work?

A technique to consider in rare cases when conventional surgery is impossible

Conventional and surgical endodontic therapy are established as predictable clinical procedures that save teeth with pulpal disease.1,2 Such teeth would otherwise be extracted. When a tooth's pulp is irreversibly injured or infected subsequent to caries, cracks, trauma, or leaky restorations, endodontic therapy or extraction are the only viable options. While conventional endodontic therapy has been shown to have an excellent survival rate (97% over an 8-year period),3 this initial procedure can occasionally fail to address the entire source of infection, resulting in persistence of periapical symptoms.

When symptoms are not resolved after conventional root canal therapy and the cause is determined to be periapical and of microbial origin, surgical endodontic approaches through microsurgical apicoectomy and retrofilling have been shown to offer a last chance to save the tooth. Fortunately, the outcome of these microsurgical procedures has improved dramatically over the past 2 decades. This is largely due to advances in material science and surgical armamentarium, as well as improved diagnosis and triage of failed conventional therapy. As a result, higher success rates can be expected from these surgical procedures.2,3

However, in a small segment of failed root canal cases, when conventional surgical access to the apex for an apicoectomy is not possible, an alternative option called intentional replantation may still save some teeth. Intentional replantation is a procedure by which the tooth is gently extracted, the apicoectomy and retrofilling procedure are performed extraorally, and the tooth is replanted in the alveolar socket. The two most important factors for successful intentional replantation procedures are short extraoral time (less than 10 minutes) and atraumatic extraction. When strict adherence to protocol is combined with the proper case selection, a high success rate can be expected from this procedure.

Indications

Whenever surgical access for apicoectomy is not possible (anatomical challenges), the options of intentional replantation or final extraction should be presented to the patient. Intentional replantation is a viable option only when all of the following criteria are met:

1. The original root canal procedure cannot be non-surgically or surgically revised with retreatment or apicoectomy with a reasonable chance of success (eg, when adequately treated root canals with coronal obstructions are failing).

2. A high-quality coronal restoration is present and there is no coronal leakage.

3. The infection is localized to the apex and no periodontal disease or cracks/fractures are present.

4. The tooth's root(s) allow(s) easy extraction and easy replantation after extraction (no sharp curvatures or thin roots and ideally conical roots).

5. The patient is fully informed of the risk and the required postoperative care, is motivated, and has realistic expectations of the success rate.

Once these criteria have been met, where a conventional apicoectomy is not possible, an intentional replantation can be attempted to save a tooth with persistent periapical disease following root canal therapy.

Case Presentation

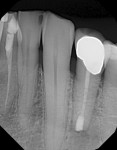

A 56-year-old male patient presented to the author's clinic with the chief complaint of pain in the mandibular left quadrant and minor swelling. History and clinical examination revealed that the mandibular left first premolar (tooth No. 21) had a 3-year-old root canal and a new crown. The patient explained that the tooth never felt normal after root canal therapy and recalled a poor dental experience during the original treatment with his dentist. In clinical tests, all teeth tested normal, except tooth No. 21, which was sensitive to percussion and palpation and exhibited radiographic evidence of a root canal fill several millimeters short of the apex (Figure 1). A periapial radiolucency was also present at the apex of this tooth. A 3-year-old, well-sealed coronal restoration was also noted.

Due to the inadequate root canal fill, non-surgical endodontic retreatment–ie, revision through the crown–was the recommended treatment option for saving this tooth. Since basic endodontic principals had not been achieved during the original root canal therapy, a non-surgical revision was assessed as the most predictable way to address the remaining bacteria in this tooth. Unfortunately, due to patient's poor experience during the initial root canal treatment by his dentist, he rejected this recommended retreatment. Surgical apicoectomy was recommended next but was also rejected due to the small, but possible, risk of nerve damage in this area. The patient opted for extraction without replacement with either an implant or a bridge, as he wanted to minimize dental treatment.

Given the patient's decision to lose this savable tooth and not replace it with a restorative option, intentional replantation was finally offered as a last resort. It was explained to the patient that the tooth would be removed, and if the root did not fracture during the extraction process and the crown remained intact, there was a chance that the surgical apicoectomy procedure could be performed outside the mouth and the tooth replanted. As long as the tooth had to be removed anyway and the periodontal condition was normal, and since the tooth had a straight conical root with a well-sealing coronal restoration, the prognosis was deemed good as long as the tooth and the crown were able to survive the atraumatic extraction procedure.

The atraumatic extraction procedure required for intentional replantation involves the removal of the tooth in such way that damage to the cementum on the root surface is minimized. As a result, excessive use of root elevators is generally discouraged. The tooth should be gently loosened and removed with slow forceps movements, with emphasis on preserving the viability of cementoblasts and periodontal cells on the root surface. Intrusive and excessive bucco-lingual forces that can potentially crush the cementum should also be minimized. This extraction procedure generally takes longer than the normal extraction and is much gentler.

A surgical scalpel was used to perform a fiberotomy to minimize damage to the soft-tissue attachment through blunt dissection (Figure 2). Minimal elevator use is recommended with emphasis on not notching or damaging the cementum. Forceps handles were secured gingival to the crown margins but not too deep on the root. The tooth was then removed following expansion of the elevator motion (Figure 3), and the root surface was examined extraorally under high magnification. The tooth was manipulated only by holding the crown (Figure 4); contact with the root surface was minimized. A small granuloma attached to the apex was removed with the aid of cotton pliers. The root surface was kept moist and hydrated throughout the extraoral time with sterile physiologic saline. Once the root surface had been examined under high magnification and root cracks and fractures were ruled out, apiceoctomy was performed using a 1557 SaberCut™ Bur (Brasseler USA, www.brasselerusa.com), and 3 mm from the root end was removed (Figure 5).

Following apicoectomy, a 3-mm deep retropreparation was prepared into the root canal using a surgical-length #2 round bur on a slow-speed handpiece (Figure 6 through Figure 8). It's important to locate and retroprep all portals of exit from the tooth. Multi-rooted teeth may require one or more retropreparations in each root depending on the number of canals. The oval canal's isthmus was also prepared.

Once retropreparation was complete, it was filled using the "Lid Technique,"2 which combines the injection of two bioceramic formulations, the EndoSequence® BC RRM™ (Root Repair Material) (Brasseler USA) with the EndoSequence® Putty Fast Set (Putty-FS). The RRM was injected to the depth of the retropreparation with the aid of a 90º bent acid-etch syringe tip (Ultradent Products, www.ultradent.com) and a thin layer of Putty-FS was placed on the cavosurface margin to seal the RRM (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Excess was removed using a small brush (Figure 11).

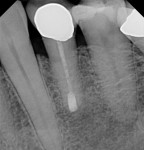

After suctioning the developed clot in the alveolar socket, the tooth was replanted back in the socket and the patient was instructed to close on a small piece of gauze between his teeth and to stay closed for 1 hour (Figure 12). This helps develop a new clot that helps stabilize the tooth. The alveolar bone around the tooth was gently squeezed back into position in case it had expanded during the extraction procedure. The total extraoral time of 5 minutes was noted. An immediate post-operative radiograph showed the retrofilling (Figure 13). The 6-month follow up radiographs and clinical pictures showed healing of the periapex and adequate gingival health (Figure 14 and Figure 15). The patient returned for a different dental procedure in a different tooth 6 years later, which allowed an additional recall radiograph to be obtained, confirming long-term healing and stability of the tooth 6 years following intentional replantation (Figure 16).

Discussion

The modern intentional replantation procedure has come a long way and has been shown to have a very good success rate.4 When strict adherence to selection criteria is combined with atraumatic extraction and apicoectomy and retrofill of all portals of exit in extraoral times less than 10 minutes, a predictable outcome can be expected. However, clinicians should focus on trying to save the tooth via less invasive ways such as conventional retreatment or apicoectomy, which have been shown to have a higher success rate, and reserve intentional implantation for when the other two procedures are not possible options. In cases where surgical access to the periapex has a high chance of nerve damage due to anatomical proximity of the inferior alveolar nerve or the mental nerve to a tooth's apex or when the root inclination is too lingual or too far back in the jaw to allow adequate visualization, this procedure can be attempted.

Postoperative care for this procedure is limited to minimizing damage to the alveolar socket and having the patient bite on the tooth until a clot is formed. In author's experience, rigid or physiologic fixation using ligatures or splints is rarely needed. Patients should be instructed to close teeth together if they feel movement of the tooth out of the socket immediately after the procedure and as needed thereafter. Occasionally, a figure 8 suture over the occlusion surface of the tooth or the use of hard periodontal dressing bucco-lingually can help stabilize the tooth temporarily until reattachment is achieved. Guidelines for antibiotic use are currently not clearly defined in the literature; however, since use of antibiotics is recommended following avulsions, it may be prudent to prescribe them in these procedures as well. Follow-up care and visits are recommended at 1, 3, and 6 months following the procedure. If the tooth is excessively loose or shows signs of reinfection during these follow-ups, it should be removed and discarded at once.

Conclusion

Conventional apicoectomy or non-surgical retreatment is always a first choice for cases with persistent periapical symptoms after root canal therapy. However, in some cases, due to anatomical challenges or contraindications for surgery or retreatment, an intentional replantation procedure can be offered as an alternative to full extraction. Case selection is the most important criteria for success; the most significant selection criteria include non-fractured teeth with conical roots, lack of periodontal pathology, and intact, well-sealing coronal restorations. Atraumatic extraction and extraoral times less than 10 minutes will help make intentional replantation a predictable procedure for teeth with persistent periapical symptoms with a history of conventional root canal therapy. The presented case demonstrated long-term retention in the oral cavity. A clinical surgical video of the presented case in this article is available for viewing online.5

About the Author

Allen Ali Nasseh, DDS, MMS

President, RealWorldEndo™

Clinical Instructor, Department of Restorative Dentistry and Biomaterial Sciences

Harvard University School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Private Practice

Boston, Massachusetts

References

1. Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a large patient population in the USA: an epidemiological study. J Endod. 2004;30(12):846-850.

2. Nasseh AA, Brave D. Apicoectomy: The misunderstood surgical procedure. Dent Today. 2014;34(2):130-138.

3. Kim S, Pecora G, Rubinstein R. Comparison of traditional and microsurgery in endodontics. In: Kim S, Pecora G, Rubinstein R, eds. Color Atlas of Microsurgery in Endodontics. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 2001:5-11.

4. Nimczyk SP. Re-inventing intentional replantation: a modification of the technique. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13(6):433-439.

5. Nasseh AA. CBL#14: Intentional replantation of a mandibular premolar. RealWorldEndo website. https://realworldendo.com/videos/cbl-14-intentional-replantation-of-a-mandibular-premolar. Accessed March 18, 2015.