Quality Quadrant Dentistry

Success relies heavily on an excellent post-preparation impression that accurately captures all of the details needed for fabrication.

Performing exceptional quadrant dentistry requires attention to detail in several areas. One of the most crucial elements is the post-preparation impression. Achieving the correct occlusion, fabricating well-made restorations, and being confident of the work is challenging in itself. Applying some simple techniques to ensure a successful outcome can lead to more satisfaction with the end result. This article is intended to review some issues general dentists deal with on a daily basis. Diagnosing the need for crowns is routine for most, but the goal to consistently deliver predictable results can be a challenge. Selecting the proper impression material and using the ideal technique will deliver flawless results time after time. Vinyl polysiloxane and polyether are currently considered the materials of choice for making fixed and removable prosthodontic impressions.1 The following case highlights an impression style that will prelude the “photo finish” clinicians intend each case to become.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old woman presented with a chief complaint of bite pain and cold sensitivity in the lower right quadrant (Figure 1). After evaluating teeth Nos. 29 through 31, it was evident that several areas of decay were present on all three teeth. Radiographic evaluation confirmed the clinical findings (Figure 2). The author’s initial recommendation was to complete a new patient evaluation and then develop a master plan that would identify all of the areas of concern. After a comprehensive examination and development of a master plan that was agreed on by the patient, treatment began in the lower left quadrant.

A thorough comprehensive examination was performed to confirm whether or not the patient had healthy joints and a stable occlusion upon which to build. She had both, with a slight hit-and-slide from centric relation (CR) to maximum intercuspation (MI) occurring on teeth Nos. 2 and 31. Because some equilibration was needed, the author decided to prepare the teeth first and then equilibrate to save time (performing equilibration on models first). The recommended treatment for teeth Nos. 29 through 31 was full-coverage restorations with the understanding that root canals might be necessary. After removing the existing restorations, decay, and properly building up the teeth, the author prepared 1.5 mm of axial reduction with a diamond chamfer bur (856-016, Brasseler USA, https://www.brasselerusa.com) (Figure 3).

The impression technique comprised using an Ultrapack number 00 cord (Ultradent, https://www.ultradent.com) with epinephrine, completely submerged around the teeth. An Ultrapack number 0 cord that had been soaked in Hemodent was packed on top of the first cord and allowed to sit for 5 minutes. Then, the second cord was removed and the impression was taken.

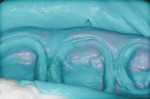

This gingival displacement technique has been demonstrated elsewhere.2,3 The flowability of light-body material is critical to the quality of impression that will be produced. For this reason, the author chose to use Flexitime® by Heraeus Kulzer (heraeus-dental-us.com) (Figure 4). The Light Flow offers an extremely low contact angle on a level similar to polyether. This product is similar to a wash with impressive flowability characteristics. In the author’s opinion, this type of material produces great results in quadrant dentistry because it crawls into all of the desired areas. Readers may have seen other articles on impression techniques advocating blowing the light body on the impression after it has been dispensed to make sure it flows into all the desired areas, but the author finds that the flowability of Flexitime makes this extra step unnecessary. The Light Flow was injected around and into the sulci around each tooth. Flexitime Heavy Tray was then loaded into a full-arch tray. The author recommends using cheek retractors when taking full-arch impressions (Figure 5). This will help to maintain a dry field while placing the impression material. Working time is also very important in performing efficient and quality everyday dentistry. Clinicians, as well as patients, do not want to wait all day for the impression to set, nor do they want it to set before the assistant can finish filling the tray. Flexitime has an in-mouth set time of 2.5 minutes, which is a good middle ground. The full-arch tray will allow better management of occlusion and proper excursive movements. As can be seen in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the detail of the margins is clearly demarcated, providing the foundation for an exceptional end result.

After the impression was taken, study models were mounted on a semi-adjustable articulator with verification of CR. Mounting full-arch models will afford the clinician the ability to better perfect the occlusion and manage excursive movements (Figure 8 and Figure 9).4 The all-ceramic crowns were fabricated using e.max® (Ivoclar Vivadent, https://www.ivoclarvivadent.us) (Figure 10) and cemented with conventional cement. Verifying the occlusion and checking the fit completed the process, and the author found excellent-fitting final restorations (Figure 11).

Reaching the desired level of quality when preparing single or multiple units for restoration is much simpler by employing the proper technique and materials. By following the process outline above, clinicians will be able to prepare, impress, and be confident about their final restorations. In addition, providing the laboratory technician with the most accurate impression will reduce the number of retakes and remakes, helping to ensure final restorations of the highest caliber.

References

1. Christensen GJ. Ensuring accuracy and predictability with double-arch impressions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1123-1125.

2. Perakis N, Belser UC, Magne P. Final impressions: a review of material properties and description of a current technique. Int J Perio Rest Dent. 2004; 24:109-117.

3. Stewardson DA. Trends in indirect dentistry: 5. Impression materials and techniques. Dent Update. 2005;32:374-384.

4. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1989.

About the Author

William “Bo” Bruce II, DMD

Private Practice

Simpsonvillle, South Carolina

Affiliate Professor

Medical University of South Carolina

College of Dental Medicine

Charleston, South Carolina