Simplifying Implant Surgical Stents for the Partially Edentulous Arch

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS; Douglas Dompkowski, DDS

Proper implant placement has become less of a prosthetic dilemma with the use of surgical stents.1-3 Surgical stents provide communication between the surgeon and restoring dentist, so that the implant is placed at the ideal prosthetic position and angulation. This article will address simple techniques for the fabrication of surgical stents.

Implant surgical stents for the partially edentulous arch can range from the simple to the complex with varying costs andtechnical expertise involved in fabricatingthem. Simple stents vary from use of dentureteeth to metal tubes in an acrylic or vacuformtemplate. These require minimal technical expertise and are relatively inexpensive to fabricate.

Stents used in partially edentulous arches have the benefit of gaining stability from the remaining teeth in the arch. When standard radiographs and clinical evaluation determine that there is adequate bone height and width, a simple surgical stent can provide the guidance required to position the fixtures properly.

Treatment of the partially edentulous arch with dental implants is less of a challenge than treatment of the fully edentulous arch.4-6 Surgical stents can be broadly divided into two basic types: restrictive and non-restrictive.

A restrictive stent guides the surgeon in the exact position and angulation of implant placement. The benefit of these stents is that the restoring dentist receives the implants placed in the exact position they planned when the surgeon uses the guide for placement. A non-restrictive stent allows the surgeon more latitude and the result may be an implant placed at an angulation or a position that complicates the restoration process. As such, the authors advocate preplanning and the use of restrictive surgical stents.

The use of metal tubes to guide the osteotomy drill is not a new concept and has been addressed in simple to complex stent designs. These have pros and cons to the basic concept. The metal tubes do not allow the osteotomy drill to diverge from the trajectory of the tube and, because of their hardness, the drill cannot create shaving debris as can be observed with pilot holes through denture teeth.

An ideal stent using metal guidance tubes would, therefore, require only enough resin/acrylic to stabilize the stent on the remaining teeth to retain the metal tube and allow the surgeon a clear visualization of the crest where the osteotomy drill is making contact. The Guide Right™ (DePlaque, Victor, NY) system provides a metal or ceramic tube to be incorporated into a stent quickly and inexpensively. It is composed of guide posts and various guide sleeves for planning and fabrication of implant surgical stents. The posts have a 2-mm portion that corresponds to a 3/32-inch drill used to create the pilot hole on the cast. Additionally, a magnetic post is provided for use with the open sleeves in both a straight and offset version. A set of guide posts is also provided for use with the ceramic sleeves that mimic the other posts discussed.

Denture teeth are placed into the edentulous space of the cast and affixed with wax to stabilize the tooth. If immediate implant placement at the time of extraction is planned, then the intact tooth is left on the cast or the missing portions of the tooth are built up using composite.

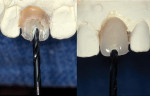

A 3/32-inch twist drill is placed into a slow-speed handpiece and a pilot hole is created through the denture tooth, spacing it at the center of the tooth in both the buccal/lingual and mesial/distal dimensions (Figure 1). Angulation should follow the long axis of the adjacent teeth so that the implant parallels the roots of those teeth and is not directed into the natural teeth. The denture tooth is next removed from the cast and a guide pin is inserted into the pilot hole in the cast (Figure 2). This is performed to verify the position and angulation and, if necessary, correction may be performed at this time before the stent is fabricated.

A stainless steel guide sleeve is slipped over the guide post and the bracket is positioned on the lingual of the cast (Figure 3). Triad gel (DENTSPLY International, York, PA) (or other appropriate material) is applied to the bracket and lingual of the adjacent teeth, carrying it over the incisal edges (or occlusal surfaces) of the adjacent teeth to provide stability from lateral displacement of the stent intraorally, and then light-cured. The acrylic should extend over the incisal or occlusal surface to provide stability when the stent is placed intraorally (Figure 4). The guide post is removed and the stent removed from the cast to finish and polish the peripheral edges.

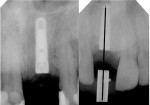

The completed stent is disinfected in cold sterilizing solution and is ready to try in intraorally to verify fit and stability (Figure 5). A radiograph is taken with the stent in place to verify trajectory compared to the adjacent natural tooth roots (Figure 6). After local anesthetic placement, the initial osteotomy is created with a 2-mm pilot drill for the implant system being used (Figure 7). This may be done either flaplessly or with a traditional flap, depending on the practitioner’s preference. The stent is removed, a sterile guidepost is inserted into the osteotomy intraorally, and a radiograph is taken to verify implant position (Figure 8). Should redirection be necessary, additional correction can be made at this time.

Normal implant surgical protocol is followed and the osteotomy is enlarged to the desired diameter and the implant is placed. A radiograph may be taken at this time with the stent placed intraorally to document alignment of the stent’s sleeve and long axis of the implant (Figure 9).

The Guide Right open sleeves are ideally designed for clinical situations when vertical heights will not permit the osteotomy drill from being inserted into the sleeve within the stent. The open buccal aspect of the sleeve allows an additional 3 mm of clearance for the drill to be inserted (from the buccal) without interference from the opposing arch.

The stent is fabricated in a similar manner to the standard Guide Right surgical stent except that a magnetic post is used in place of the standard guide post. Either a denture tooth is placed into the edentulous space or one of the Guide Right set-up disks is used. Should the set-up disk be used, a disk corresponding to the diameter of the tooth to be placed is placed onto the cast. The hole in the set-up disk positions the center of the implant in the center of the space so that the final crown has equal flare mesially and distally. A 3/32-inch twist drill is introduced through the center of the denture tooth or set-up disk to create the hole in the cast. A magnetic guide post is placed into the hole in the cast and an open sleeve is placed on the guide post with the retention portion of the sleeve positioned to the lingual. It is suggested that the open portion of the sleeve may be directed toward the mesial/buccal (position the retentive element to the distal/lingual) as this will aid insertion of the osteotomy drill. The stent is completed by application of Triad gel or other appropriate acrylic to complete the stent as previously outlined.

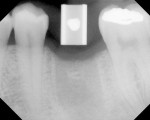

The stent can then be inserted and a radiograph taken to verify positioning of the guide sleeve (Figure 10). During surgical use of the stent, the osteotomy drill is guided along the closed portion of the sleeve to allow it to be guided by the stent (Figure 11). After development of the osteotomy with the open sleeve stent, the implant is placed based on the implant manufacturer’s instructions (Figure 12).

Implant dentistry is a prosthetically driven treatment modality andcommunication between the restoring dentist andsurgeon is critical to treatment success. Theuse of surgical stents communicates the desiredposition and angulation of the implant so thatthe restorative phase of treatment does not encounter problems that can compromise the esthetic outcome or complicate oral hygiene for the patient.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Sean Meitner forhis assistance with the manuscript and the images.

References

1. Binon PP. Treatment planning complications and surgical miscues. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(7 Suppl 1):73-92.

2. Rosenlicht JL. Simplified implant dentistry for the restorative dentist: integrating the team approach. Int J Dent Symp. 1995; 3(1):56-59.

3. John V, Gossweiler M. Implant treatment planning and rehabilitation of the anterior maxilla: Part 1. J Indiana Dent Assoc. 2001; 80(2):20-24.

4. Small BW. Surgical templates for function and esthetics in dental implants. Gen Dent. 2001;49(1):30-34.

5. Wat PY, Chow TW, Luk HW, Comfort MB. Precision surgical template for implant placement: a new systematic approach. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2002;4(2):88-92.

6. Mason WE, Rugani FC. Prosthetically determined implant placement for the partially edentulous ridge: a reality today. J Mich Dent Assoc. 1999;81(9):28-37.

7. Cehreli MC, Sahin S. Fabrication of a dual-purpose surgical template for correct labiopalatal positioning of dental implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2000;15(2): 278-282.

8. Kopp KC, Koslow AH, Abdo OS. Predictable implant placement with a diagnostic/surgical template and advanced radiographic imaging. J Prosthet Dent. 2003;89(6):611-615.

About the Authors

Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS

Private General Practice

Silver Spring,Maryland

Douglas Dompkowski, DDS

Private Practice limited to Periodontics and Implant Dentistry

Bethesda, Maryland

Clinical Associate Professor

University of Maryland Dental School

Baltimore, Maryland